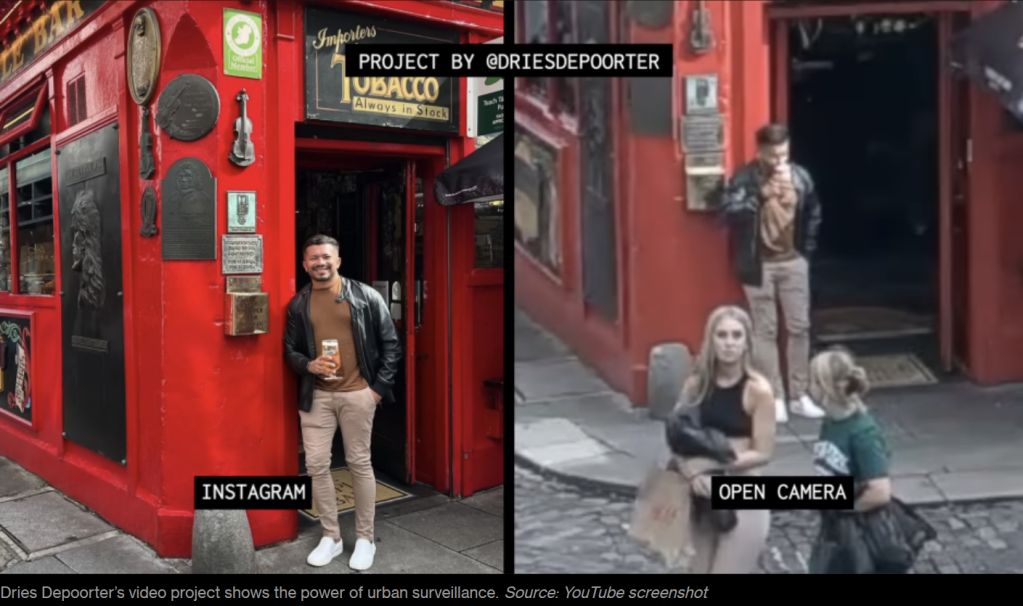

Dries Depoorter’s art project ‘The Follower‘ is a clever use of publicly available video and image data and a fun glimpse into the how those “casual” Instagram shots are really taken. It’s also a somewhat harrowing warning about what information us members of the public are unknowingly sharing in a world where tools can process and ‘understand’ data in ways not generally available just a few years ago.

First up Depoorter recorded the images from what are essentially publicly accessible CCTV cameras hosted by Earthcam, such as this one in Dublin, and another in New York. These cameras are naturally associated with a particular location.

People’s Instagram photos are also often tagged with a location, and many of them are publicly accessible. So he downloaded any Instagram photos that were taken around the same geographic location that the video feeds came from.

He then used freely available facial recognition software to match up the two sources of image data, identifying moments of the video footage that captured the person from a particular Instagram photo. Winding the video footage back a little meant that he could watch the person wander into the frame, faff around deciding how to set up the perfect Insta shot before going ahead and taking it.

All of this is probably legal, at least in many jurisdictions, as it used only publicly available inputs. Lawyers have advised him that this is fair use.

Instagram doesn’t sound too excited about its product being involved – it’s possible that technically he broke their terms of use, tbd. Many of the clips he shared publicly, including the original Youtube video, have subsequently been removed “for copyright reasons” – the NYT reporting that these are claims made by Earthcam as they consider the footage to be theirs. GDPR may also be relevant given Depoorter lives in the EU.

But legal or otherwise, I think this feels extremely creepy to most of us. I’m confident that most people who happen to wander through Times Square and other popular locations aren’t aware that a live video of them is being transmitted to the world at large via public webcam sites. They’re certainly not given consent. And if any of them are aware, they might not have top of mind the idea that any fairly technical internet user might have the ability to isolate and identify them; determining exactly who they are, where they were, when that was, and watch them doing whatever it was they were doing at that point in time.

I didn’t find out exactly what software was used to match the faces between the webcam video and the Instagram photo, but a quick look at Github reveals nearly 4000 openly accessible repositories that relate to face recognition. The first of which explicitly says it can be combined with other libraries to do real-time face recognition of this kind.

These repos are a tremendous and generous resource for those of us who have cause to or simply enjoy playing with data, analytics, artificial intelligence and related topics. But of course there’s nothing to stop folk with worse intentions from leveraging the code.

A lot of people of course use their real names and other identifiers on their Instagram profile meaning that Depoorter’s unknowing stars were also “deanonymised” to him in a data sense. The artist had a lot more sense than to include the names or social media handles of his unwitting subjects – often just “normal” folk going about their days with not more than an average level of clout chasing. But that’s naturally not a given for any less public or future people or groups that decide to perform similar exercises. The New York Times managed to track down one of the people from Depoorter’s project, who turned out to be a French teacher and later consented to be featured in their article.

Beyond clever and important art projects, it doesn’t take much imagination to think of substantially more horrific uses for the ability to secretly identify who is where in the world plus have video of their activity that they weren’t aware was being recorded. At that point the precise legality isn’t all that meaningful – bad actors aren’t likely to respect GDPR, even where it does apply.

My general default is to be a big fan of publicly accessible data. The more data we have access to, the more we can learn and the greater the good we can do with it. But for almost all use-cases, data that identifies individual people – including videos attributable to them – should only exist and be shared with their explicit consent. And it needs to be an informed type of consent, whereby people understand, for instance, what today’s tools can do with a random webcam video of you.

In this case, it’s not even clear to me how to request consent. Sure, on the Instagram side of things people can and probably have technically ticked yes to a set of terms and conditions. In theory, they’re able to stop sharing their location, at the expense of losing some of the utility the app provides. Improvements can be made there. But how to deal with consent issues on the Earthcam side of things is less obvious to me. The site’s purpose is apparently to “transport people to interesting and unique locations around the world that may be difficult or impossible to experience in person”. That probably does have some value. But you shouldn’t need to tick a box or agree to your data being captured, processed and shared in order to cross the street.

People are rightfully wary of organisations such as the police using facial recognition technology en masse without considering the implications. Well resourced and trained organisations no doubt have resources and tools that go way beyond what was done here. But this piece of data-based art has highlighted that the same kind of ethical and practical considerations around the video and image data routinely captured of you are of relevance way beyond what it takes the resources of a state or big business to do.